Gefeoht æt Hæstingum

This post was made on 14th October 2024, 958 years to the day in 1066 when King Harold and the English army were defeated at the Battle of Hastings by William the Duke of Normandy.

It can be argued that this battle is the most consequential event in the history of England, but as the years march on each anniversary of this calamitous defeat passes with little comment. William the Bastard, as he's called by all true Englishmen 😉, became William the Conqueror and Harold is now largely forgotten or dismissed as vainglorious and a usurper.

On 25th September, only 19 days before the defeat at Hastings, Harold had won a resounding victory at Stamford Bridge (Gefeoht æt Stanfordbrycge), near York, over a Norwegian invasion force led by King Harald Hardrada and Harold's brother Tostig Godwinson (that's a whole other story!). That victory had been preceded on 20 September by the defeat of the English (led by the northern earls Edwin and Morcar) at the Battle of Fulford, just outside York, which had led to Harold marching from London to York to face Harald and Tostig.

Following the victory at Stamford Bridge, the Norman army led by William landed in Pevensey, in Sussex, on 28th September. This meant that Harold had to march his remaining troops south again, some 260 miles, to face a much more difficult foe.

It's almost impossible to imagine what Harold and his followers had just gone through, and the enormous effort of will that must have been needed to face (for some) a third battle within a month. Battles at which the future of England was at stake.

The annals of Florence of Worcester contain this account of how Harold reacted when learning of the Norman landing:

Therefore the king at once, and in great haste, marched with his army to London. Although he well knew that some of the bravest Englishmen had fallen in the two former battles, and that one-half of his army had not yet arrived, he did not hesitate to advance with all speed into Sussex against his enemies. On Saturday, 22 October1, before a third of his army was in order for fighting, he joined battle with them nine miles from Hastings, where his foes had erected a castle. But inasmuch as the English were drawn up in a narrow place, many retired from the ranks, and very few remained true to him. Nevertheless from the third hour of the day until dusk he bravely withstood the enemy, and fought so valiantly and stubbornly in his own defence that the enemy's forces could make hardly an impression. At last, after great slaughter on both sides, about twilight the king, alas, fell. There were slain also Earl Gyrth, and his brother, Earl Leofwine, and nearly all the magnates of England.

Writing in The Deeds of William, duke of the Normans and king of the English William of Poitiers describes the start of battle and how the outcome could, initially at least, have been very different:

From all the provinces of the English a vast host had gathered together. Some were moved by their zeal for Harold, but all were inspired by the love of their country which they desired, however unjustly, to defend against foreigners. The land of the Danes who were allied to them had also sent copious reinforcements. But fearing William more than the king of Norway and not daring to fight with him on equal terms, they took up their position on higher ground, on a hill abutting the forest through which they had just come. There, at once dismounting from their horses, they drew themselves up on foot and in very close order. The duke and his men in no way dismayed by the difficulty of the ground came slowly up the hill, and the terrible sound of trumpets on both sides signalled the beginning of the battle. The eager boldness of the Normans gave them the advantage of attack, even as in a trial for theft it is the prosecuting counsel who speaks first. In such wise the Norman foot drawing nearer provoked the English by raining death and wounds upon them with their missiles. But the English resisted valiantly, each man according to his strength, and they hurled back spears and javelins and weapons of all kinds together with axes and stones fastened to pieces of wood. You would have thought to see our men overwhelmed by this death-dealing weight of projectiles. The knights came after the chief, being in the rearmost rank, and all disdaining to fight at long range were eager to use their swords. The shouts both of the Normans and of the barbarians were drowned in the clash of arms and by the cries of the dying, and for a long time the battle raged with the utmost fury. The English, however, had the advantage of the ground and profited by remaining within their position in close order. They gained further superiority from their numbers, from the impregnable front which they preserved, and most of all from the manner in which their weapons found easy passage through the shields and armour of their enemies. Thus they bravely withstood and successfully repulsed those who were engaging them at close quarters, and inflicted loss upon the men who were shooting missiles at them from a distance. Then the foot-soldiers and the Breton knights, panic-stricken by the violence of the assault, broke in flight before the English and also the auxiliary troops on the left wing, and the whole army of the duke was in danger of retreat.

But, it was not to be so and the 'D' version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle pithily summarises the battle and its catastrophic outcome for the English:

Then Count William came from Normandy to Pevensey on Michaelmas Eve, and as soon as they were able to move on they built a castle at Hastings. King Harold was informed of this and he assembled a large army and came against him at the hoary apple-tree, and William came against him by surprise before his army was drawn up in battle array. But the king nevertheless fought hard against him, with the men who were willing to support him, and there were heavy casualties on both sides. There King Harold was killed and Earl Leofwine his brother, and Earl Gyrth his brother, and many good men, and the French remained masters of the field, even as God granted it to them because of the sins of the people.

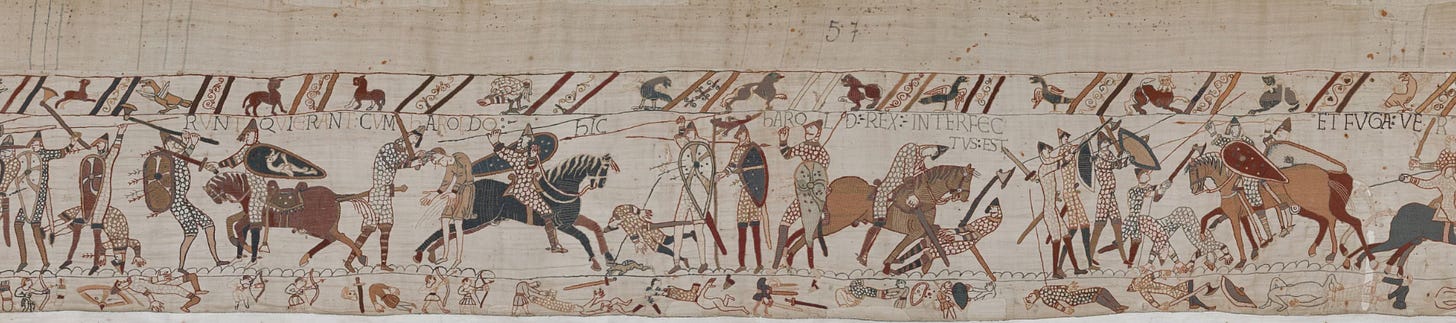

The Bayeux Tapestry famously illustrates, from a Norman perspective, the events leading up to the battle and the battle itself. Scene 57 shows the fateful moment where Harold, fighting to the end with his battle-axe, is cut down by a Norman knight.

Following further resistance from the English, William was eventually crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey on 25th December. There were further failed rebellions across England in following years, but by 1070 England's fate was sealed and the Anglo-Saxon era finally gave way to the Anglo-Norman era.

The date of 22nd October is an error in the annal.