The Rohirrim and The Wanderer

Tolkien's love of the Anglo-Saxons and the Old English language.

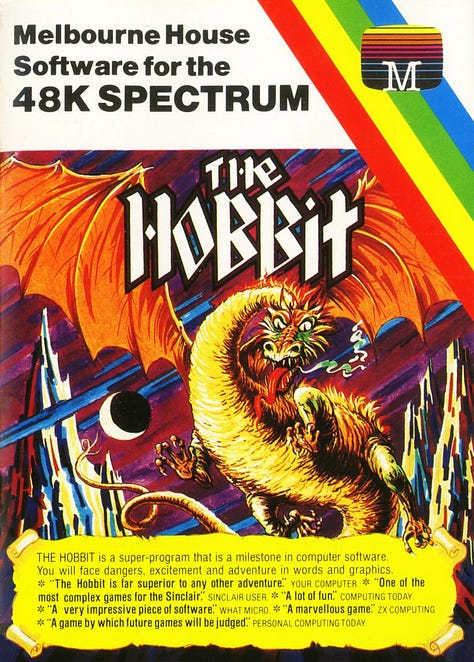

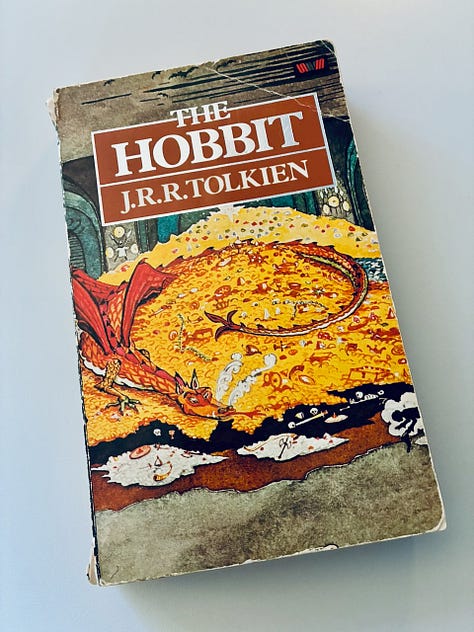

Back in 1982 some marketing whiz had the bright idea of bundling a copy of The Hobbit with the computer game of the same name, an amazing act of foresight that undoubtedly led to many more sales of Tolkien’s other works.

I don’t recall having heard of J.R.R. Tolkien before receiving a ZX Spectrum and this game as a Christmas present in 1983, and I suspect that many like myself found the book more engrossing in the long term than the game itself.

Even to an uncouth teenager the maps, runes, and the strange story itself all suggested a bigger picture both in fiction and in reality. Following The Hobbit I read The Lord of the Rings in 1984 but didn’t return to Tolkien for many years until I had started to become interested in the Anglo-Saxons and the Old English language. Even then, with neither little research or understanding, it was apparent to me that much of Tolkien’s work was rooted in Anglo-Saxon (and wider Germanic) history and mythology and the more Tolkien I read and the more I learnt about the Anglo-Saxons the clearer that became.

There has of course been much written about this subject and I probably have little to add other than the observation that when rereading, in particular, The Lord of the Rings, passages that reflect Tolkien’s own love and affection for the Anglo-Saxons, their language, and the landscape of northwestern Europe often jump of the page.

A good example from chapter VI of book three, “The King of the Golden Hall”, is shown below. Gandalf, Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli have arrived at Edoras where Théoden King of Rohan resides in his great hall named Meduseld.

‘Look!’ said Gandalf. ‘How fair are the bright eyes in the grass! Evermind they are called, simbelmynë in this land of Men, for they blossom in all the seasons of the year, and grow where dead men rest. Behold! we are come to the great barrows where the sires of Théoden sleep.’

‘Seven mounds upon the left, and nine upon the right,’ said Aragorn. ‘Many long lives of men it is since the golden hall was built.’

‘Five hundred times have the red leaves fallen in Mirkwood in my home since then,’ said Legolas, ‘and but a little while does that seem to us.’

‘But to the Riders of the Mark it seems so long ago,’ said Aragorn, ‘that the raising of this house is but a memory of song, and the years before are lost in the mist of time. Now they call this land their home, their own, and their speech is sundered from their northern kin.’ Then he began to chant softly in a slow tongue unknown to the Elf and Dwarf; yet they listened, for there was a strong music in it.

‘That, I guess, is the language of the Rohirrim,’ said Legolas; ‘for it is like to this land itself; rich and rolling in part, and else hard and stern as the mountains. But I cannot guess what it means, save that it is laden with the sadness of Mortal Men.’

‘It runs thus in the Common Speech,’ said Aragorn, ‘as near as I can make it.

Where now the horse and the rider? Where is the horn that was blowing? Where is the helm and the hauberk, and the bright hair flowing? Where is the hand on the harpstring, and the red fire glowing? Where is the spring and the harvest and the tall corn growing? They have passed like rain on the mountain, like a wind in the meadow; The days have gone down in the West behind the hills into shadow. Who shall gather the smoke of the dead wood burning, Or behold the flowing years from the Sea returning?

Thus spoke a forgotten poet long ago in Rohan, recalling how tall and fair was Eorl the Young, who rode down out of the North; and there were wings upon the feet of his steed, Felaróf, father of horses. So men still sing in the evening.’

Marvellous stuff I’ll hope you agree. It is well known that Rohan is explicitly modelled on the Anglo-Saxons, and a couple of obvious correspondences in the passage above are:

The Old English words simbel (always or ever) and myne (mind) are used by Tolkien for the flower simbelmynë (evermind) which grows on the burial mounds of the dead kings.

When Tolkien wrote The Lord of the Rings it was thought there were also sixteen burial mounds at Sutton Hoo, and a short distance away at Rendelsham there was a great hall complex overlooking the river Deben (and descriptions of great halls are found in Beowulf and elsewhere in Old English verse and prose).

The Wikipedia page for Rohan1 has many more examples.

However, due to my long and slow journey to learn Old English2, a couple more things really made me sit up and take note (emphasis mine):

When Tolkien says of Aragorn “Then he began to chant softly in a slow tongue unknown to the Elf and Dwarf; yet they listened, for there was a strong music in it.”

When Legolas says “That, I guess, is the language of the Rohirrim for it is like to this land itself; rich and rolling in part, and else hard and stern as the mountains.”

The poem spoken above by Aragorn is adapted from lines 92 to 96 of the Old English poem The Wanderer:

‘Hwǣr cwōm mearg, hwær cwōm mago? Hwǣr cwōm mǣþþumgyfa? Hwǣr cwōm symbla gesetu? Hwǣr sindon seledrēamas? Ēalā beorht būne, ēalā byrnwiga, ēalā þēodnes þrym. Hū sēo þrāg gewāt, genāp under nihthelm swā hēo nō wǣre.’

My favourite translation of that is the one found in A Choice of Anglo-Saxon Verse3, edited by Richard Hamer:

‘Where is the horse now? Where the hero gone? Where is the bounteous lord, and where the benches For feasting? Where are all the joys of hall? Alas for the bright cup, the armoured warrior, The glory of the prince. That time is gone, Passed into night as if it had not been.’

I can’t think of a better description of what Old English sounds and feels like than the one that Tolkien gives. It’s a language with a strong music in it which is rich and rolling in part, and else hard and stern as the mountains. And for that reason alone I think it’s worth the effort to learn at least a little Old English, and to read The Hobbit to your small children or grandchildren.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rohan,_Middle-earth

https://ancientlanguage.com/old-english/

https://www.faber.co.uk/product/9780571325399-a-choice-of-anglo-saxon-verse/